Of all the trends decision makers from the public and private sectors track, demography is the most predictable, since births, deaths, and even migration tend to follow patterns and paths. Here are four trends I foresee for 2024, drawing on my backgrounds in both political science and demography. Much as it pains me, to keep this newsletter short I’ve dropped the nuance—check out my chapters on youth and on migration in 8 Billion and Counting for a deeper discussion and a more extensive literature review.

Demographic trends portend a world of greater conflict in 2024. In sub-Saharan Africa, continued population growth amid resource strains and poor governance will lead to continuing communal violence and coups in the region. In higher income countries with low fertility and robust migration, the weak response to aging, fracturing societies will lead to greater polarization and domestic discontent, and growing support for far-right parties.

Demography is powerful, and no view of 2024 or beyond is complete without taking population dynamics into account. However, the line I repeat time and again is that there’s nothing inherently good or bad about demographic trends—it’s the response that matters. We know this because two different countries (regions, cities, pick your poison) can experience similar demographic dynamics but with different economic, political, and social outcomes. (See my discussion of migration for what I’m on the verge of conceding is the first exception to that rule.) To that end, I’ve tossed out some policy prescriptions for each trend. I’d love to hear what else you’d add to those and what other demographic trends you see for 2024 in the comments section.

I’m taking a break from the newsletter in December to focus on book writing and I’m pausing all paid subscriptions, so you won’t be charged. Looking forward to picking back up in the new year and I thank you for all of your support!

Africa will remain a hotspot for instability

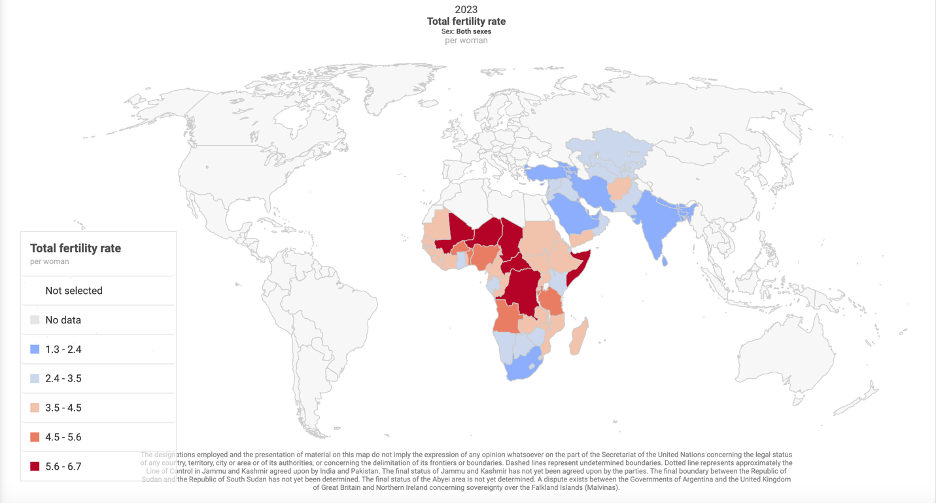

There is a relationship between high fertility and political instability, and only one region of the world where high fertility countries are concentrated: sub-Saharan Africa.

Countries with very youthful populations are more likely to experience armed civil conflict and to lose liberal democracy, even if they briefly gain it. They’re also more likely to experience coups. According to research by Richard Cincotta, age-structural models lead us to expect successful coups to occur in somewhere between four and nine countries every five years for the next decade-and-a-half. There have been 7 coups since 2021 in sub-Saharan Africa and the lowest total fertility rate among the group is in Gabon, which still has a median age of only 21 years. Countries with median ages under 25 years have a higher likelihood of breaking out into revolutionary conflicts, a group that includes most countries in Western and Eastern Africa (but not Northern, and not all of Southern Africa); several countries in Central Asia, like Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan; Haiti; Guatemala; and some island states in Oceania, like Papua New Guinea.

The core argument of my most recent book was that there’s a global demographic divide, and that divide even shows up within the region of sub-Saharan Africa, where even in Kenya fertility is down to 3.24, while it remains as high as 6.7 in Niger (the sub-continent’s highest). Once a country’s total fertility rate dips below 3 children per woman on average there’s a lower probability of instability but there are still 57 countries in the world with fertility that high (although that’s down from 87 in 2000.) Any way you slice it, these populations will balloon over the next few decades.

Population growth in the context of poor economic conditions and poor governance increases risk of conflict. When youth are politically and economically excluded, they have a lower opportunity cost for participating in violence. Social exclusion matters, too: poor economic prospects preclude some young men from getting married, further lowering their opportunity cost. One note: there is some evidence that those who occasionally find work in the informal sector, who want to work but are unable to find jobs, are more at risk of protesting or engaging in violence than those who are chronically unemployed.

Longer term prospect: As long as policies to increase school enrollment for girls, make reproductive healthcare available, and end child marriage continue, fertility rates will continue to come down—but the size of and level of commitment to those investments will determine how far and how fast fertility rates fall. With greater income-earning opportunities for women outside the household and more jobs available for men, too, Africa’s youth bulge can be leveraged for economic development. With most of the world aging and shrinking, African nations have a unique demographic advantage.

Policy recommendations: Invest in women and girls. Strengthen the human capital base in sub-Saharan Africa and allow families to invest more in health and well-being of individual members, which will help them generate more household income. Ending child marriage, educating women and girls, and increasing opportunities for earning outside the household help lower fertility, but these goals are good in and of themselves—lowering fertility rates doesn’t need to be the aim. The US has partnered with coastal West African countries as part of its Strategy to Prevent Conflict and Promote Stability. I hope they’re thinking of the demographic connections as they work towards peace in the region.

Expect continued conflicts between pastoralists and farmers in West Africa and the Sahel

Clashes between migratory pastoralists and settled farmers are a major source of communal violence in sub-Saharan Africa, which of course spills over into additional communal violence and balloons into larger-scale conflicts. It’s not just areas where land and water resources are stressed where conflict breaks out, rather it’s often neighboring areas where pastoralists have moved to seek new and better resources where the violence happens. This is something to keep in mind when mapping potential hotspots.

Given high fertility and environmental strains across West Africa and the greater Sahel, conflicts between farmers and herders will be especially acute there. For example, Senegal has one of the youngest median ages in the world, 18 years, and decades of population growth ahead. Senegalese pastoralists have always migrated with the seasons but now are moving into new areas because of climate change, and months sooner than previously. Population growth has increased demand for farmland across the region and closed off some areas to grazing. Political developments—rise of settled farmers’ political influence, takeover of land by larger agribusinesses, and jihadism—have effectively made some areas off-limits.

These migrations bring communities with previously limited contact into greater contact with one another, increasing the risk of clashes. In Nigeria, conflicts between farmers and pastoralists have killed more people than Boko Haram.

Longer term prospect: Continued population growth and environmental changes (from land use and climate changes) will only make the risk of conflict higher in West Africa and the Sahel in the coming years.

Policy recommendation: Strong, good governance will dilute the power of these demographic and environmental trends. NGOs and governments can help coordinate placement of pastoralists and serve as mediators, as Peter Schwartzstein notes for the Wilson Center, but it’s tough (the Senegal example comes from his excellent research).

Populism will find fuel in opposition to migration, especially in Europe

With White European populations aging, nativist fears of being replaced by those of different ethnic or racial groups will continue to rise and result in greater success for anti-immigration parties at the polls. If you’re in the business of futures, remember that it’s not the actual population numbers that matter so much as the perception, so it’s more important from a political science perspective to track rhetoric and mobilization around anti-immigrant sentiment, than to track just changing ethnic composition of a country. Parties and individuals play on fear and foment the sense that demographic change is accelerating due to the combination of low fertility and high migration. In some cases, it really is accelerating, but it’s the perception and fear that are most important for driving political reactions, not the demography itself. I’m writing a book on this that looks historically and cross-regionally and can tell you that it happens irrespective of actual demographic change.

In the liberal democracies of North America and Europe, both actual influxes of migrants and media-fueled perception of influxes will continue to feed anti-immigrant sentiment in 2024. With the left generally clinging to a pro-immigration line, that leaves the right to monopolize rhetoric about toning down immigration (but they’re unlikely to do so, see below). That means the net effect of continued immigration by racial and religious groups different than the majority population will continue to deliver the right increased voter share, and, when the rules of the game allow, electoral victories. And all of this means more polarization and disagreement.

Populist political parties across Europe have seen greater successes over the recent past, and that will continue in 2024 and beyond. One recent example: Switzerland’s right-wing People’s Party, or SVP, gained nearly 3% over its 2019 vote share, garnering 28.6% of the vote, which makes it the country’s most popular party—as it has been for the last two decades. With the populist parties the only ones who seem keen to curb immigration, they are attracting more voters.

Fears of demographic replacement are absolutely not limited to Europe or North America. Even Tunisia’s president has invoked fears of replacement by ‘black Africans’ from sub-Saharan Africa who’ve moved north on the continent in hopes of making it to Europe. But with the combination of low fertility and increasing migration of non-Europeans, Europe will be at the epicenter of demographic populism.

There’s a divide between what the population experiences and perceives and what the policy makers want. The UK has experienced record migration under its Conservative government, and that’s post-Brexit. This matters because the composition of migrants, not just the volume, is changing, and fueling backlash against migration among the population, even as the politicians continue to argue that immigrants are necessary to fill labor shortages in the health care industry (demand will only increase as the population ages). Instead of continental Europeans, there are more Indians and Nigerians coming to Britain, heightening the sense that the country’s demography is changing, and amplifying the impact of immigration on local communities.

Policy makers may increase the volume of immigration at the national level for macroeconomic or humanitarian reasons, but they don’t provide adequate resources at the community level. I just returned from a trip upstate New York over Thanksgiving, and learned that some elementary school classrooms will receive refugees from multiple countries, but without adequate support to help the students adjust to American classrooms, including behavioral and academic expectations. (Don’t forget, these children and their families have gone through immense trauma, too.) This is hard on teachers, American students, and newcomers, and fuels support for politicians who say they’ll reduce immigration—in the US, it fuels support for Trump.

Policy recommendation: I teased that I may be conceding an exception to the rule that it’s not the demographic trend that matters so much as what societies do with it, and this is it. Policy reforms would matter when it comes to migration, but democratic policy makers aren’t going to do what it takes to ease the strains of migration and capitalize on the potential benefits, not in 2024 and not in the years that follow. The two-party system of the US and UK (effectively) doesn’t incentivize politicians to actually make useful reforms (like reforming the understaffed and underfunded asylum system in the US). In contrast, the multi-party systems more common in Europe make space for parties running on primarily anti-immigrant platforms. When they gain power, these parties will try to curb overall numbers, rather than institute the tedious and numerous reforms needed to make migration work for all. So, I could make tons of policy recommendations but they’ll never happen because POLITICS, so why bother? On the whole, we need to stop fetishizing sweeping changes to immigration and start tweaking the margins to make the system work better.

Continued low fertility in high income countries

Finally, fertility rates will continue to go down or stay low. In Asia, patriarchal norms aren’t going anywhere any time soon and they have a huge dampening effect on women’s desire to marry and have children. In one of the best discussions on this I’ve read, Yen-hsin Alice Cheng argues that across Asian societies, Confucianism pressures fertility lower because it emphasizes patriarchal values and credentialism. The former makes marriage increasingly unattractive for young women, in particular, who have experienced rising social status and economic independence over the last few decades. The latter makes childbearing unattractive because it is so labor-intensive—mothers (generally) must devote a large share of their time and household resources to their children’s education. China’s rhetoric calling for women to return to the home and abandon their rising status shows just how out of touch the almost completely male leadership is with Chinese women’s ambitions and the competitive market economies in which they are embedded (even as they are also embedded within hierarchical and patriarchal societies). It is really only during the last decade that the pace of rising marriage age has increased in China (while it was faster earlier in other Asian countries), but it’s on the rise and since non-marital births are still highly taboo in Asian societies there’s no baby boom coming.

Policy recommendations: I’m really stuck with this one. I’ve always been an institutionalist scholar (as my feelings about party systems clearly shows) but when it comes to fertility rates norms just seem so much more powerful. Parental leave policy by itself isn’t enough: Japan and Korea have two of the most generous paid paternity leave policies among the OECD but uptake is really low among fathers—3% in Japan and 5% in Korea (and only 22% for mothers in Korea versus 86% for Japanese mothers).

Cost of living by itself isn’t a great predictor of fertility rates, as this post from demographer Anne Morse points out, but more so social norms around what constitutes a good life set against cost of living.

And so much for higher Nordic fertility rates: Marika Jalovaara reports a near 1/3 decline in Finland’s total fertility rate since 2010. We’ve always been told it’s the norms of equality in the Nordic countries plus policies that reinforce those norms that’s responsible for the region’s relatively higher fertility. Now what are we to think?

Have a wonderful holiday season and I’ll see you here in the new year.

Jennifer, I'd like to draw your attention to my last post, which describes a new global photo journalistic project on demography and ageing. Maybe this is interesting for you. https://dorotheelebrun.substack.com/p/1-in-6-by-2030-how-dry-demographic

Feel free to reach out.