How the business world needs to prepare for global aging

The world of 8 billion is "older" than ever before, and the trend continues

Welcome, new subscribers! I know many of you found me when world population hit 8 billion and if you’re reading this, congratulations! We survived to see the other side of that day, despite doomsayers of prior eras. Of course, it’s the people rich enough to have internet access that are least affected by the imbalance of population and resources, but that’s a topic for another day.

In this week’s newsletter, I offer a few ideas for how businesses can adjust to global population aging and a snapshot of how today’s and tomorrow’s seniors differ from those of yesterday. A shortened version of this newsletter appeared in the Harvard Business Review in the heels of the 8 billion milestone. It was quite a week for me, news-wise. If you’d like to share that link directly I’m sure HBR would be thrilled and you can do so by clicking here. This version includes some examples that got cut, but that I think are useful illustrations.

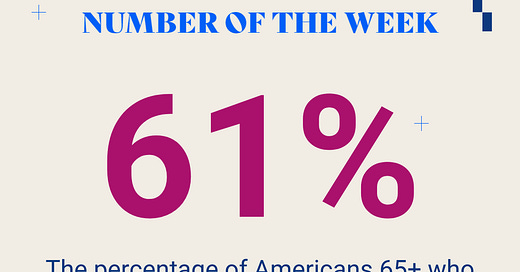

According to a Pew Research Center survey from early this year, the percentage of older people who own smartphones and use the internet is way up, and the gaps between young and old are shrinking. This is important to note as we contemplate the workforce of tomorrow. I wish Pew had looked specifically at ages 55-70, as that’s the group I think we need to understand better. Since those 65+ are lumped together, I’m going to assume smartphone and internet usage is actually much higher for those on the younger end of that age group. I wonder what the inflection point is, age-wise, for declining usage…75? 80? This is another example of how our analysis is only as good as our data, and how we need to reconsider age categories in data collection.

In this case, my own headline. A shorter version of this appears as:

According to the latest UN reports, two-thirds of the global population live in countries with below-replacement fertility rates, while average lifespans continue to grow. This means that many populations are rapidly aging, and will soon begin to shrink (if they haven’t already). At the start of this century, 32 countries had a median age above 35 years. By the end of this decade, that number will more than double. And in 25 of those countries, half the population will be more than 45 years old.

In many respects, we may think of the future as uncertain. But unlike so many technological, political, and economic shifts, demographic trends are extremely predictable. Our aging population is all but inevitable — and it will have a substantial impact on global labor pools, markets, and the future of work, with several important implications for business leaders:

1. An Aging Workforce

Due to falling fertility rates, countries across Asia, North America, and Europe have fewer new entrants into the workforce every year. To compensate, companies need older employees to stay on longer, but they also need to invest in training and development to help these older workers acquire new skills, as well as into additional accessibility and safety measures such as wearable exoskeletons to help older workers safely lift heavy loads on farms and in factories.

Not all aging countries have robust immigration, and even those that do still face labor challenges. An additional option is automation to replace or augment certain roles. One trend is in a “digital workforce”—tools that offer fully virtual sales associates, customer service representatives, and even companions for the elderly. I remember learning about robotic cats that sat on the laps of elderly Japanese and monitored their vital signs early in my career and the technology has obviously improved since then. Between growth in AI capabilities and shifting demographic trends, these new technologies have the potential to become an increasingly substantial component of the modern workforce. Japan’s economy has continued to be one of the world’s strongest, even as the country has led the globe in aging, and Japan is a prime example of using automation and robotics to offset labor losses.

2. An Aging Customer Base

Over the last decade, the global 70+ population grew by 627 million, from 5% of the total population up to 12%. In another decade, 16% of the eight billion people on earth will be over 70. That means tremendous opportunities for products and services that serve this older demographic. My colleague Bradley Schurman writes of some of these opportunities in his book, The Super Age.

The most obvious sector for growth is health care, where demand for geriatric medicines, primary and specialist care, and related products, such as wearable glucometers or electrocardiograms, is set to continue to expand. Walgreens is one company banking on that demand.[DD1] [S2] Under CEO Roz Brewer, the company is scaling up its primary health offerings, aiming to make healthcare more accessible to a wider range of people, and, she hopes, make health care less expensive overall. I think refocusing away from “age” and towards “health” is the key to navigating our new demographic reality. While life expectancy has risen, in many places, healthy life expectancy lags, meaning that finding ways to support the health and wellbeing of this growing demographic isn’t just a business opportunity — it will be critical for policymakers and government leaders as well. For example, older people in the U.S. are more likely to live in rural areas, where health care is often less accessible. In Arkansas, Maine, Mississippi, Vermont, and West Virginia, more than half of the older population is rural, suggesting substantial and growing demand for elder-focused health care services in these markets. Models like the Walgreens clinic that combine retail and health services could fill an important gap.

Aging customer bases can mean more opportunities for some savvy business owners. For example, aging homeowners may look to downsize, or adult children may look to buy homes with room to house aging parents. As demographics shift, realtors may increasingly benefit from developing and signaling expertise in helping buyers and sellers through these transitions, whether by obtaining professional development certifications or through other specialized efforts. My friend Natalie, a realtor in Huntsville, Alabama, noticed the need for a centralized hub for seniors wanting information on relocation to the city that’s been named the most desirable place to live in the United States. So, Natalie founded Rocket City Seniors, modeled after Rocket City Moms, a website devoted to helping parents of younger children connect and find resources. As the market slows, this specialization gives her a leg up on her peers.

3. Shifting Retirement Norms

Of course, age is just a number. When it comes to retirement norms, expectations around how long workers expect to stay on the job don’t necessarily correspond with lifespans. For example, purely based on age, Japan is the world’s oldest country, with 31% of its population 65 or older. In contrast, only 22% of the French population is 65 or older. As such, one might expect that a greater proportion of Japan’s population would be in retirement — but in fact, a combination of differences in work cultures, social contracts between governments and their citizens, and a host of rules and policies mean that the average retirement age in France is 10 years younger than in Japan: 61 years old versus 71. As a result, around 29% of France’s workforce has effectively retired, compared to just 24% of Japan’s.

But legal changes to retirement ages are slow to take hold. In recent years, both the Netherlands and Ireland cancelled plans to increase retirement ages for pensions to match lengthening life expectancies. This is common and democracies are slow to make pension reforms since politicians pay the price for even suggesting upward revisions. But demography is increasingly out of sync with these regulations. Creating some sort of mechanism to help older workers who choose to delay retirement will be critical for employers, governments, and citizens.

For instance, many older workers who are not yet ready to retire have begun demonstrating increasing interest in semi-retirement. In a recent survey of working Baby Boomers, the vast majority said they’d like to pursue some form of semi-retirement, with 79% expressing interest in a flexible work schedule, 66% in transitioning to a consulting role, and 59% in working reduced hours. But just one in five said their employer offered any of these semi-retirement options, suggesting substantial opportunity for employers to differentiate themselves in the competition for talent by offering non-traditional career paths. One company that does is Principal Financial Group, based in Des Moines, Iowa. One of Principal’s programs allows employees aged 57 and older with a minimum of 10 years with the company to phase into retirement, going from full- to part-time work. Another program brings back those who have been retired for at least 6 months for part-time work. The company benefits, but so do the employees: if they work at least 20 hours a week they’re eligible for health and retirement benefits.

When seeking to understand a given labor market, leaders must consider not just how old people are, but also the flexibility of employment options and the varied rules and cultural norms that may influence different countries’ true retirement ages. Anyone in the business of risk assessment needs this full picture.

4. Shifting Global Markets

Finally, it’s important to recognize that our common assumptions around different countries’ demographic makeups may be out of date. At the turn of the century, countries such as Japan, Italy, and Germany were among the world’s oldest populations — but today, Thailand and Cuba are just as old, with Iran, Kuwait, Vietnam, and Chile close behind. In a decade, we can expect smaller cohorts of young people in these countries to begin to enter the market as workers and as customers, thus increasing the average age of these populations.

These are critical considerations when identifying new markets for investment. Different countries will respond differently to these shifts, and business leaders would be wise to pay attention not just to the demographic trends of a given market, but to how its leaders are likely to react to them. With more and more elders to care for, will governments take on the financial responsibility? Or will companies or individuals be expected to bear the burden? A country’s approach to managing its aging population can influence its potential as a talent pool or customer base in substantial and nuanced ways.

The Future Is Clear

Today’s business leaders and policymakers face countless sources of uncertainty — but when it comes to demographics, the future is clear. The reality of our globally aging population is evident now, as once a population’s fertility rate goes below replacement level (an average of two children per woman), it stays there. Barring massive immigration from places that still have young and growing populations, such as Ethiopia or Nigeria, that most likely means a less-populated future for the majority of countries on our planet.

This clarity enables foresight and planning of a sort not possible in many other domains, in which shifts may be harder to predict. There’s a lot of fear around population aging, and determinist, pessimistic rhetoric is increasingly widespread — but the effects of this trend on our businesses and governments will depend on how we prepare today. To adapt to our aging populations, business leaders and policymakers alike must acknowledge these realities, understand which factors are certain and which can be influenced, and proactively invest in shaping the future.

This week I’m recommending the New Security Beat blog out of the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program (ECSP). I’ve been reading (and occasionally writing) for it for years, and have assigned many pieces to students in my environmental courses. ECSP brings a diverse group of scholars and practitioners to the blog, so readers can hear from writers who’ve experienced the links between population-health-environment-security all around the world. ECSP is one of the two programs I’m affiliated with during my 2022-2023 appointment as a Wilson Center Scholar.

Thanks for reading! If this newsletter helps you make sense of our complex world of 8 billion people, I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber, buying my latest book, or hosting me as a speaker for your organization. And if you’re just a casual reader, I’m still very glad you’re here, and thanks!

Until next time,

Jennifer