How US programs to control fertility of Southern US Blacks led to Japan’s approval of the pill 5 decades later

A tale of forced sterilization, eugenics, and the counterintuitive position of Japanese feminists

Thanks for reading! If this newsletter helps you make sense of our complex world of 8 billion people, I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber, buying my latest book, or hosting me as a speaker for your organization. And if you’re just a casual reader, I’m still very glad you’re here, and thanks!

In upcoming newsletter editions, I’ll be writing about aging and AI, how to use population in foresight, and sharing some from a co-authored book I’ve been working on for a long time, which will be published by Oxford University Press in 2025. This newsletter pulls from that project and tells a story that fascinated me when I came upon it in my research. The sources I draw from are listed at the end.

Japan did not legalize the oral contraceptive pill until 1999, just a few years after Viagra won approval. The confluence of events that led to the pill’s approval had a stop along the way in my own neck of the woods, the American South, where in 1950, Dr. Yoshio Koya, head of Japan’s National Institute of Public Health, was sent by US Army Occupation forces to study state-sponsored contraceptive initiatives targeting rural Blacks.

The story of Dr. Koya’s visit, and the evolution of Japanese attitudes towards abortion and contraception generally, is a winding one. Like many population programs, Japan’s has eugenicist roots, but plays out in ways unfamiliar to those acquainted with the Western narrative, which often puts feminist social movements at the center of abortion and contraceptive rights advocacy.

During Japan’s colonial days and the war, having lots of children was seen as a patriotic duty. Dr. Koya himself, as a student of race relations, promoted pronatalist ideas as a way to help Japanese more effectively rule over Korea. Japan’s wartime exhortation to “bear and multiply” took a turn after the war, when both American occupation forces, headed by General Douglas MacArthur, and Japanese elites, grew panicked over Japan’s high birth rates and rapid population growth.

The idea that population growth caused poverty, and poverty caused communism would become the refrain of Cold War attitudes about foreign population growth among the US elite. But Japan’s elite, who were working towards Japan’s economic recovery, were worried, too. Among scholars who’ve studied the family planning discourse in Japan around the end of WWII, there is debate over the true motivations behind various stances, but differing opinions existed.

Newsweek reports that the American occupation authorities placed the birth control problem “off limits,” as it was so contentious. That wasn’t entirely true. At the same time that they barred Margaret Sanger from visiting Japan, they also supported Dr. Koya’s visit to the US South.

As one of Japan’s leading health experts, Dr. Koya was close to the center of the nation’s debate over whether or not to support birth control. He firmly believed that birth control to prevent pregnancies before they happened was a superior alternative to abortion, “interrupting” (in Japan’s parlance) pregnancy after the fact. Maybe he felt that way because he was a Christian, maybe because he truly worried about the effects on women’s health if abortion was used as birth control, as he stated many times, or maybe for some other reason.

Whatever the reason, the US said the Japanese solution to overpopulation should be home-grown. And what did they decide? Initially, it was a NO to birth control, and instead the main population policy took form as the 1948 Eugenic Protection Law (EPL). The EPL legalized abortion, meaning that physicians could interrupt pregnancy for economic reasons or concerns over the mother’s health.

While the US and many other countries have had decades-long fights about abortion, in Japan it was legalized with comparatively little debate as a means of controlling population growth. And Japanese women did indeed use abortion. The first measures I could find were 1.17 million abortions in 1955, for a rate of 50.2 per 1000 (by 2005 it was 10.3). The birth rate halved in around a decade from 34.3 births per 1,000 to 17.2 by 1960 (scholars’ estimates range from 10-13 years).

Not everyone thought the EPL was sufficient. Japan’s Population Planning Council was established in 1949 and immediately recommended all restrictions on family planning be removed. The Diet—Japan’s law-making body—rejected this recommendation and the council was soon dissolved. But Koya persisted.

Koya thought Japan could devise a better solution, and received support from his pen pal Dr. Clarence Gamble (of Proctor & Gamble), a prominent US eugenicist and supporter of family planning, who worked with Margaret Sanger to launch the “Negro Project” in 1938 to reduce birth rates of Southern, rural Blacks in the US. Koya, who also held a post as Vice President of the Japanese Association of Racial Hygiene, traveled to the US February through April of 1950, visiting with White officials and scholars involved in efforts to lower birth rates among the Black populations in Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky, Georgia, and North Carolina.

Gamble and Koya had an extensive correspondence and Gamble fronted money to first help Koya visit the US, then for Koya to conduct his own studies back in Japan. These became known as his famous Three Villages Study. What Koya took from his visit, and then applied in his study, we would recognize as some of the hallmarks of effective community health programs: a field-trial method that made accessing contraception free and easy to access (a method still used) and nurses employed as social care workers, all organized by government offices. Reading more deeply into this, it’s clear to me that this is yet another example of how a scientific approach to population legitimated intervention into private reproductive lives in order to solve what was portrayed as an “objective problem.” In this case, the “objective problem” was Japan’s overpopulation, and the solution was controlling that population through a variety of means. Individual agency about reproductive choices is almost nowhere to be found in these stories, which involve US philanthropists, scholars, doctors, and government officials—including military officers—and their Japanese counterparts. Public health initiatives were scaffolded by these often racist and eugenicist ideas, a legacy that impedes public health progress in some communities even today.

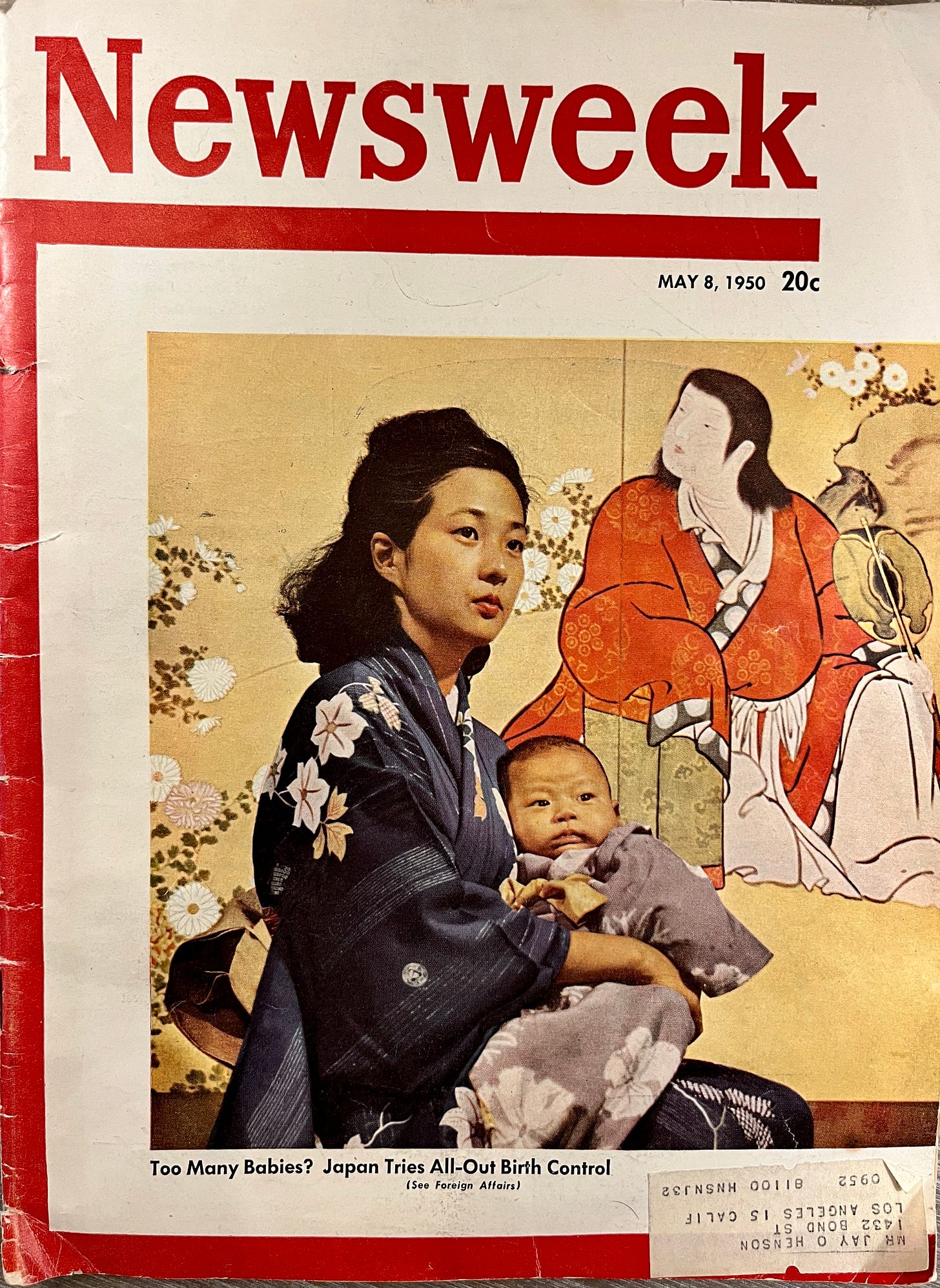

The month following Koya’s visit, which seems to be coincidental, as Koya is never mentioned, the cover of Newsweek magazine would feature a Japanese mother and child with the headline: “Too Many Babies? Japan Tries All-Out Birth Control.”

The Newsweek reporter, Compton Packenham, describes observing the work of one of Japan’s EPL screening committees, established to review cases of individual women desiring abortion and determine whether or not they qualified to receive an abortion under the 1948 EPL, mostly its economic reasons clause. By 1951, Japan’s cabinet members started to support contraception over abortion and condom use eventually became widespread.

The EPL was a means of controlling reproduction and its legacy tarnished efforts to legalize the pill in Japan, which had been blocked by an unlikely group: Japanese feminists. These feminists opposed the pill because they saw it as anti-feminist, placing the burden of contraception on the female and subjecting her body to side effects from hormones. Rather than liberating for women, the pill was liberating for men, they argued. The feminists weren’t alone in their opposition. Profits from condom sales and from abortions, concerns that the pill would promote “sexual immorality,” concerns over side effects, and, during the late 1980s and 1990s, worries that use of the pill would facilitate spread of HIV/AIDS, all prevented widespread uptake of the oral contraceptive pill, according to research by Miho Ogino.

Looking at the history of Japanese population trends alongside its reproductive politics, we see more evidence that governments are always chasing that elusive “sweet spot” of population and are rarely satisfied. Japan went from “too many” to “too few” in the blink of an eye, just as China, South Korea, and many other states did. By the time Japan approved the pill, Japanese women had on average 1.3 children—what we consider super-low fertility (a rate of 2 would “replace” both parents).

Reckoning with the legacy of the Eugenic Protection Law

At the landmark 1994 International Conference on Family Planning in Cairo, a Japanese woman with disabilities spoke out against the Eugenic Protection Law, garnering international attention that, along with domestic social movement activism, forced changes in the law just 2 years later. In 1996, the EPL was renamed the “Maternal Protection Law” and its eugenic provisions repealed to only allow voluntary sterilization and abortion.

In June 2023 (just 2 months ago), Japan’s Diet published a report on the EPL that revealed that around 16,000 people were sterilized without consent under the law over the 48 years of its existence, including two nine-year-old children.

Sources:

The most comprehensive description and analysis of Dr. Koya’s visit is by Aiko Takeuchi-Demirci in the journal Southern Spaces in 2011, but the visit was also chronicled by Koya himself, who published extensively in English, and by other scholars at the time, such as C.P. Blacker. I also consulted Miho Ogino’s chapter, “From Abortion to ART: A History of Conflict between the State and the Women’s Reproductive Rights Movement in Japan after World War II,” in one of my favorite books, Reproductive States.

The number of people with Hispanic roots is growing in the US, with Venezuelans growing by 169% from 2010 to 2021, while Mexicans are growing the slowest, at only 13% over that time. Fewer Hispanics in the US are immigrants, with US births to Hispanic parents outpacing growth in immigration of that group. Between 2010 and 2021, Hispanics in America were more likely to speak English (72%), be US citizens (81%), and have a bachelor’s degree (20%).

This newsletter is a space for me to work through ideas and play with data so the writing is always a bit loose. Please forgive any errors, but let me know if you spot them!

Wow, this was an interesting and well-written article that I had zero knowledge of before. Governments finding the "sweet spot" is so challenging, and it seems like it is often a pendulum that swings back and forth - hopefully eventually toward a "good" center. Thanks for writing this!