This week’s newsletter explores one aspect of gerontocracy—rule by the old—by focusing on youth political engagement. What’s interesting about this line of research and this line of argument is that questions about gerontocracy aren’t limited to countries with aging populations. As we’ll see, even in countries with high proportions of youth there’s a sense that politics has been hijacked by older generations and the concerns of young people aren’t being heard.

By the way, it’s already summer here in the South, and that means this newsletter will go to every other week. I hope you take time away from the computer as I plan to and get some rest and relaxation!

In the US, as in many countries, youth voter turnout pales in comparison to that of older voters—in the most recent US presidential elections rates of Americans aged 60+ were 20-30 points higher than those of 18-29-year-olds. Here’s the big question: Does it matter?

FYI: I used Prof. Michael McDonald’s corrected data, but he provides raw data if you want to do your own correcting and calculations.

There are two equally prevalent stories about youth participation among journalists and academics today. One is a tale of historic political disengagement: For every Malala or Greta there’s millions of teenagers stuck to their phones and completely disengaged from politics. Just look at voter turnout rates, this side argues, which in many countries, such as Japan, are abysmal compared to those of older cohorts. To pad the numbers, Japan lowered the voting age from 20 to 18, but youth still stayed away from the polls.

The other viewpoint on youth political participation is much rosier. Voting is important, but political participation comes in many other forms—campaigning, protests, strikes, petitions, social media—and these are forms youth are more likely to engage in. Climate change, in particular, has galvanized youth action.

There’s a third view that I think needs more focus. Youth may care about politics, but not participate because they feel the system is too broken and their concerns won’t be heard. Lack of participation doesn’t equate to apathy. Writing for a pro-EU advocacy group about low youth turnout in the recent French elections, Rayan Vugdalic notes that this year’s low turnout was second only to the 1969 French presidential elections, yet, “the historically low voter turnout rate of the 1969 presidential election followed the greatest social uprising in modern French history. Did an extremely politicised and active generation suddenly stop caring about politics a year later? Of course not.” Rayan argues that youth simply have no faith in the existing political structures and thus engage in different ways.

The feeling that the system is broken exists across the Atlantic as well. Harvard University’s spring 2022 poll of American youth showed that 36% of youth surveyed think “political involvement rarely has tangible results” and a slightly higher percentage don’t think their vote makes a difference.

How, though, do you change the system?

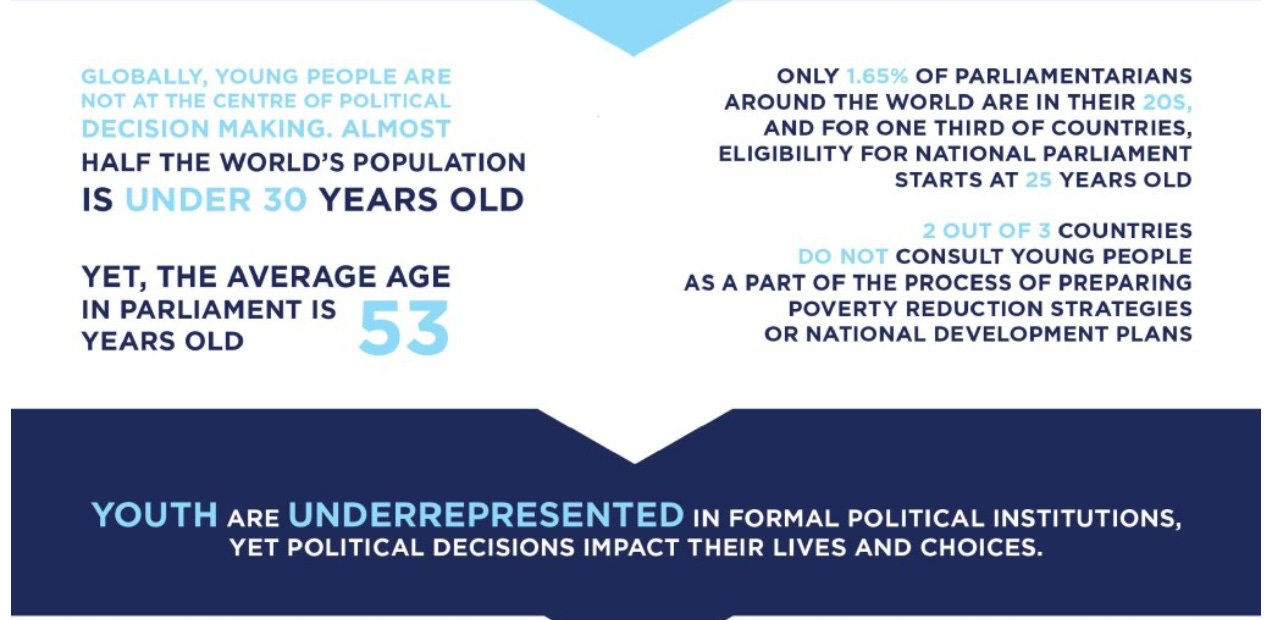

The UN clearly feels that formal participation of youth in political institutions, particularly serving in decision-making positions, is important to amplify youth voices. Just look at the stats below. Along these lines, Nigeria, where 70% of the population is under 35, has lowered the age of eligibility for some political offices.

As a researcher, I don’t think we should dismiss the importance of voting or holding office, but we should broaden our approach. In particular, we should ask: Is youth participation necessary to ensure youth interests are considered in policy making? Older voters don’t only vote in their own personal interests. Presumably (and survey data bear this out, as I found in my dissertation), they also care about education of their grandchildren, a healthy planet, etc.

We also need to think about disentangling race and gender from age. While youth is a stage of life that everyone passes through, race and gender are not universal. How many of the issues of today’s “youth” are really issues of race, since in many countries younger generations are far more ethnically diverse? With fertility at historically low levels in places like South Korea, Taiwan, and the US, how many “youth” issues are really about gender and the failure of social norms around work and family life to keep up with economic changes?

ICYMI: My new book is apparently the antidote to Elon Musk’s theories about underpopulation and Inside HigherEd thinks everyone should read it, even if they have no time. Speaking of…

Here’s what I’m starting with for some fun summer reading. Those of you in parts of the world other than mine, hang in there. We’ll be enjoying our break in just a few days!